Nigel Jarrett

August 1, 2022

Nigel Jarrett is a former daily-newspaperman and a double prizewinner: the Rhys Davies Award for short fiction and the inaugural Templar Shorts award. His first story collection, Funderland, was widely praised. His debut poetry collection, Miners at the Quarry Pool, was described by Agenda poetry magazine as ‘a virtuoso performance’. Jarrett’s first novel, Slowly Burning, was published in 2016, as was his second story collection, Who Killed Emil Kreisler? In 2019 Templar published his story pamphlet A Gloucester Trilogy.

This year, Saron Publishers is bringing out his much-awaited long-fiction work Notes from the Superhorse Stable and Cockatrice Books his fourth story collection Five Go to Switzerland.

Jarrett also writes for Jazz Journal, Acumen poetry magazine, and many others. His work is included in the Library of Wales’s anthology of 20th– and 21st-century short fiction. He lives in Monmouthshire.

Many congratulations Nigel on your recent publication – what inspired you to write Notes From the Superhorse Stable?

A writer’s inspiration is often found in unlikely places. From the deck of a boat on an African river, Graham Greene saw a white man in a white linen suit entering a hut. Just that. From such a beginning emerged A Burnt-Out Case, his novel about redemption in the Belgian Congo.

The impetus for Notes From the Superhorse Stable had a few sources: one in my wish to write fiction in an unusual way; one in the moment I saw two foxes crossing the road at night after I ‘d driven off the Dieppe-Newhaven ferry; and another in my wife’s family-history researches. But writing lengthy prose fiction is difficult. The way those three elements came together is hard to explain, not least because Dieppe came to have a significance I never envisaged at the start.

There was no detailed plotting before I began. A quarter of the way through, the story took an unusual turn, which I followed through to completion. Writing took two years off and on. What I finished up with bore little resemblance to the vague ideas I had at the start.

Tell us a little about the book…

Notes From the Superhorse Stable is narrated by Francis Taylor, a ‘resting’ actor whose career has been virtually ended after he was attacked by a pig while making a TV documentary about medieval life. He’s working as a carer in a Gloucestershire nursing home, where his ‘notebook’ is being written. While an actor, Francis discovered a long-lost relative, Harold Taylor. Harold was once a coal-miner in South Wales and is now living in retirement near Worthing. There are foxes in his garden. One of Francis’s early roles was as the lead horse in Peter Shaffer’s play Equus.

At that point I didn’t know where the story was heading, except that non-human animals seemed to be hovering at the perimeter and making a bid for entry. And so it turned out.

Harold is ill and Francis’s on-and-off partner, Julie, is unstable. An eccentric friend of Harold is suggesting he tries a controversial way of treating his illness.

The unusual aspect of the book is in its title. Notes can be wide-ranging and sometimes off the point, if they have a point beyond the need to record an experience. Put it like this: if a novel’s third-person narrator is a woman, was she a witness to all the events she describes, even the intimate ones where she couldn’t possibly have been present?

I wanted to construct a believable scenario, in which, if my male (first-person) narrator recalls conversations, he admits to giving only their gist. How could he do other? As a note taker, a diarist, he also has his own ideas of what’s relevant. There’s a story being told but the storyteller isn’t a novelist. A different story would be written by a novelist without the digressions which Francis knows he’s including.

But what is my role in the process? What is prose fiction, and what is it trying to achieve?

Where do you draw writing inspiration from?

John Updike believed that a writer was simply a reader who ‘wanted to get in on the act’. In other words, writers for him were inspired by reading, by what had been written by others. I agree. But my writing inspiration is also drawn from my life as a newspaperman.

I was paid for the enjoyable activity of turning into written words, into news, what I’d been delegated to observe. It was therefore easy for me to do the same for my own ideas and emotions, and any need I had to explore, dramatise, and formalise them. It just happened that I was one of those journalists who read a lot and was encouraged to write by what I’d read and by how it was possible, as if from nothing, to ‘make’ something fictional with words. (Jokers will say that that’s what newspaper reporters do all the time!)

What is the most difficult part of your writing process?

Successful writing is based on discipline. I don’t mean successful in terms of book sales but in terms of having written something that pleases you. Even full-time writers, however, find it difficult to write for the same amount of time every day. I can only write when I feel like it and when I’m aware that, as Henry James put it, ‘something will always come’ if I apply myself. It usually works. The problem with this piece-meal approach is in maintaining continuity. A woman with cerulean-blue eyes on page 54 may turn out to have chestnut-brown ones four months later (in writing terms) on page 269.

Another difficulty, once the publication stage has been reached and your work is being scrutinised by an editor, is fielding criticism and having to cut or re-write. When you thought your script had been neatly packaged, its pages start falling out at random and have to be improved on and marshalled again.

What comes first for you – the plot or characters – and why?

Characters, every time. For me, they dictate the plot, such as it is at any given moment. In Notes From the Superhorse Stable, it was a while before I realised that the so-called ‘animal kingdom’ was making a pitch for inclusion. It began with the narrator’s performance in Equus, a play about the savage blinding of horses by a disturbed adolescent with a spike, and continued with a care home resident called Bob Berridge, a former bookmaker, who’d written something about the mysterious disappearance of the racehorse Shergar. The animals are as much characters as the human ones. It’s almost magical realism. But not quite.

What, in your opinion, are the most important elements of good writing?

Clarity of vision, plus an ability to transport readers to a place they had not before encountered, which they can believe in, and whose characters elicit from them human sympathy and understanding. This includes everything from kitchen-sink realism to Tolkien-style fantasy.

But it’s not all about ‘fine’ writing. In A Moveable Feast, Ernest Hemingway says: ‘I’ve been wondering about Dostoevsky. How can a man write so badly, so unbelievably badly, and make you feel so deeply?’

It would be better if we could feel deeply as a result of good, clear writing.

If you had to describe yourself in three words, what would they be?

Obsessed with Shakespeare.

What books inspired you as a young reader?

I didn’t start reading seriously until I was fifteen. In a couple of days I finished a collection of stories by Guy de Maupassant while on holiday and battened down in a rain-lashed Cornish guest house. I don’t recall reading books before I became a teenager. When I did, the book I dipped into most was Enquire Within, a ‘home’ compendium by Elizabeth Craig (I think), with its litany of explanations for pubescent angst under unlikely headings.

I read Alan Sillitoe’s The Loneliness Of the Long-Distance Runner when it came out and never realised hitherto that it was possible for a first-person narrator to assume the identity – in this case a borstal boy – of someone whom one would not have associated with the ability to write, to express himself. There was enough available reading matter written by Oxbridge graduates and friends of aristocrats; not that I had anything against them. At that time, too, I discovered Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness. Only later was I aware that there were few women writers in my completed list. Jane Austen and Emily Brontë were among the earlier ones.

What book is currently on your bedside table?

Make that ‘books’, plural.

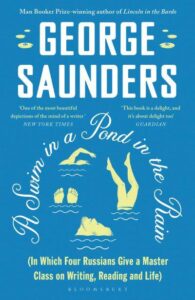

The first is A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, by the American George Saunders. It’s a write-up of the lessons he teaches at Syracuse University, New York, on the 19th-century Russian short story. Saunders is an original, with a tragi-comic take on American life. His novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, which won the Man Booker prize, is a story about the dead son of Abraham Lincoln, told by a convocation of ghosts. Perhaps only Saunders among current US writers of distinction could get away with that. It’s a masterpiece.

The second book is A Delius Companion: a 70th Birthday Tribute to Eric Fenby. I’ve been lucky enough as a writer to have been a journalist as well as an author of stories, novels and poetry. For many years I was a music critic. I still write on ‘classical’ music. Also, I review and write for Jazz Journal magazine, to which I contribute a regular column called Count Me In. The music of Frederick Delius has been a lifelong passion. A short work by him, An Arabesque, for baritone, chorus and orchestra, was given its world première at the Great Central Hall in Newport in the 1920s. The place was closed in the late 1950s/early 1960s and transformed into enlarged shops. It was the most egregious act of corporate vandalism Newport has ever witnessed, angering the conductor Sir John Barbirolli and reducing him to tears. I attended the last concert there, given by Barbirolli and the Hallé Orchestra, when he expressed his disappointment in an emotional speech.

I researched the Delius first performance and discovered that the choir involved was the wholly amateur Newport Choral Society, a finding that astonished the Delius expert, Dr Lionel Carley, when I told him. Fenby was the obscure Yorkshireman who offered his services as amanuensis when news broke in Britain that Delius, in the final stages of tertiary syphilis, was blind and paralysed at his home outside Paris and unable to compose. The story of how Fenby helped the composer in his final years is the stuff of fiction – and the subject of a Ken Russell film.

Who would be your three dinner guests?

If living: writers Graham Swift and Alice Munro, and Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis. If not: poet Emily Dickinson, entertainer Josephine Baker, and writer Gore Vidal.

Swift is almost a contemporary of mine and a writer of novels about Britain centred on the second world war and immediate post-war years. He was also first published by Alan Ross in London Magazine, as was I. Varoufakis could talk about politics and economics and offer useful comments on world events that always elude me. Vidal was an eloquent wit and Dickinson a poet who wrote in an almost proto-Modernist style. Munro might explain why her imagination is so fertile, while Baker would exude a charismatic glow to match all the other guests as well as expatiate on the loves and skirmishes of the sexes.

In what way have libraries influenced you?

I’ve never got over the amazement and good fortune of being able to borrow books for nothing. When I became a serious reader and graduated from Zane Grey to George Eliot, and books about Eliot and others of that ilk, I discovered my county reference library. I was elated when libraries began discarding old or little-read stock and offering it for sale. It seemed to happen simultaneously worldwide. I’ve bought a lot of books that way. Many second-hand purchases online turn out to have originally been public library acquisitions, often in such places as Durham and Memphis. I went through a phase of deploring the reduction of books in libraries and their replacement by ‘information’ resources. Now I’m not so angry, because there’s no point in providing a service whose use is declining. The task is to halt any decline and encourage people to read more and borrow more books from libraries, whatever they are now called.

How would you encourage children and young people to read more for pleasure?

I think there’s a link to be established or strengthened. It can begin at home but it mostly begins in school. Schools should be encouraged to form reading clubs, if they are not doing that already, as places where reading as an out-of-classroom pleasure can be promoted. Part of this exercise would involve direct appeals to parents, discounts on the price of books for children belonging to the clubs, and competitions and prizes for ‘reviews’ of books read. It’s important not to confine reading to ‘literature’: books on many other subjects – technical, sports, natural history, adventure – can encourage the reading habit.

Read our Get to Know the Author flyer for further information about Nigel Jarrett and Notes From the Superhorse Stable.

See also our Authors of the Month writing in Welsh.