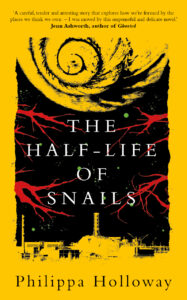

Philippa Holloway

June 6, 2022

‘Holloway has written a novel that shimmers with compassion, one that crosses borders of both nations and emotions. In telling the story of a mother’s love for her son and an intimate, searing portrayal of survival set amidst the Ukrainian Maidan Revolution of 2014, the author has crafted a tale that will linger longer than the half-life of many other books you will read this year. Holloway’s fascination with the intersection of where history meets everyday life has given us a story told with great skill, weaving together the legacy of Chernobyl and the tragedy of human arrogance. She gives us hope that each of us can act with grace and love even in the face of overwhelming disaster and a precarious world. Sadly for us, it is even more necessary for us to hear these stories today’ — Alex Lockwood, author of The Chernobyl Privileges.

What inspired you to write The Half-Life of Snails?

I was six years old when the Chernobyl disaster happened, and I was not allowed outside to play for a few days. I remember standing at the window staring up into a blue sky and wondering where the poison was, watching the cherry blossom drift from the tree onto the lawn, drift like the cloud they said was coming. Years later I was sent to do some work at a Nuclear Power Station and found myself filled with an unexpected anxiety. I realised I needed to explore these tensions, and that writing was the right way to do it. It was a way to ask questions, and find answers – if not all of the answers.

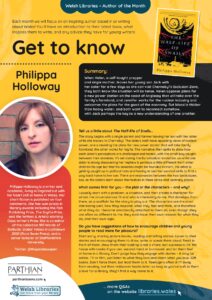

Tell us a little about the story …

The story begins with a single parent and farmer leaving her son with her sister while she travels to Chernobyl. The sisters both have opposing views of nuclear power, one is resisting the plans for new power station that will take family farmland, the other works for Wylfa, The narrative then splits to show how each sister’s perceptions are challenged and tested, with the small boy caught between their anxieties. It’s set during the Euromaidan revolution, so while one sister is slowly discovering her nephew is perhaps a little different from other children his age but that his anxieties might be founded in truth, the other is getting caught up in political riots and having to test her survival skills to find a way back home to her son. There are resonances between the two landscapes, too, as the sisters learn about themselves in these tense and contrary places.

Where do you draw writing inspiration from?

Most of my writing emerges from place – from paying attention to landscapes and buildings and communities and all the little details that might trigger an emotional or behavioural response that I can then run with. I ask a lot of questions as part of the process, about who and what might happen here, and why, and from this characters and stories are formed and tested. I seek out tensions and strong emotional connections in specific places, signs and patterns and sometimes weird meanings and interpretations of what happens there.

What is the most difficult part of your writing process?

Making the decision to cut or change something that I am emotionally invested in, but that isn’t right for the story. Sometimes you have to let things go, to move forwards, but once you take that knife to the text, what emerges is often so much better that the wound heals pretty fast.

What comes first for you – the plot or the characters – and why?

I usually start with a problem, a situation, and then create a character for whom the circumstances fit and who is interesting to me. Plot develops from there, as a scaffold for the story to play out. The characters are the most interesting part, how they respond, what they feel and think, and therefore what they do. I become emotionally attached to them all, even though they are often so different to me, they each have their own reasons for what they do, and their own logic.

What, in your opinion, are the most important elements of good writing?

Knowing what a good story feels like, and not being afraid to tell it your way. And re-writing to get there! A well-crafted story is a joy to read, and takes the reader somewhere new, so they become invested in the characters and their journeys and can experience the setting as if they are there. I always seek out books that show me something and somewhere I could never experience in real life, or help me look at familiar things afresh. The tiniest twist or slant can provide so much.

If you had to describe yourself in just three words, what would those be?

Determined, compassionate, curious. These things are not always connected, but all are great motivation for writing.

What books inspired you as a young reader?

I was a ravenous reader as a child, and would read anything and everything. I loved books about the natural world and animals, and read everything by Gerald Durrell and James Herriot, as well as fiction in which children ventured alone in the world, like Blyton’s ‘Adventure’ series. I also developed a love of horror quite early on, and remember taking Stephen King novels out of the library when I was about ten or eleven, and being consumed by the depth of his storytelling and characters, the worlds he created, as well as devouring anything by Anne Rice. I loved Patricia Highsmith too, and Douglas Adams, as well as classics like Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre – really anything I could get my hands on! I had the joy of experiencing a new generation of children’s fiction with my son, and like him love books like The Wolf Wilder, Ready Player One and The Hunger Games, and anything by Neil Gaiman.

What book is currently on your bedside table?

When I’m writing I tend to turn to books that are completely different to my own genre and style. I’m currently enjoying the Rivers of London series by Ben Aaronovitch, which were gifted to me by a friend, and are utterly captivating. I do always keep a copy of The Wolf Border by Sarah Hall close by, it’s just stunning prose and excellent storytelling.

If you could invite any three people for dinner, whom would you invite?

I know I should list famous authors or celebrities here, but honestly? It would be friends, some of whom are writers too, that I don’t see often enough, but with whom I can be vulnerable and genuine with. The meandering conversations and unpicking of issues that we care about are so valuable, and also are as much food for writing as discussing plot-lines with a famous author would be. Although I get the feeling Stephen King would be a fun dinner guest, and generous in conversation!

In what way have libraries influenced you during your lifetime?

I was educated at home until my mid-teens, and so the local library was a precious place for us. When we were very small, we used the tiny library in Skegby, which is curved round and shaped like a snail shell, and the librarians there knew us really well. We visited about two or three times a week, and I remember that tingle of anticipation on the way, and kneeling on the scratchy carpet as I flicked through the children’s books, then the thrill of venturing into the towering main fiction section as I grew up. We lived in Wales by the time I had my son, and spent hours in Bangor public library, and he too looked forward to the visits, to the delight of finding new stories. I worked in Bangor University library for a few years too while I was a student there, and especially loved the Main Arts Library.

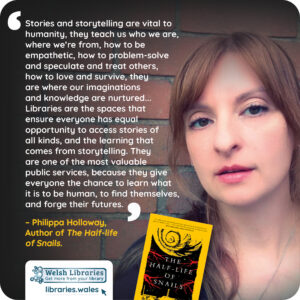

Stories and storytelling are vital to humanity, they teach us who we are, where we’re from, how to be empathetic, how to problem-solve and speculate and treat others, how to love and survive, they are where our imaginations and knowledge are nurtured…Libraries are the spaces that ensure everyone has equal opportunity to access stories of all kinds, and the learning that comes from storytelling. They are one of the most valuable public services, because they give everyone the chance to learn what it is to be human, to find themselves, and forge their futures.

Do you have suggestions of how to encourage children and young people to read more for pleasure?

Start early, sharing picture books, reading and telling stories. Listen to their stories and encouraging them to draw, write or speak them aloud. Read in front of them, show them that reading is not a chore, but a pleasure. Fill the house with books if you can, second-hand or borrowed, and let them feel at home in a library. Don’t judge how they engage with stories – it may be online, TV or film, just listen to what they love and share what you love. Gift books. Don’t force them, but lead them to it. Teenagers often drift away from reading, but then rediscover books later: so long as you’ve built in them a love for a library, they’ll find a way home to it.

Parthian are supporting the Red Cross Appeal for Ukraine by donating all their profits from the sale of the book in the UK to the Ukraine appeal. Their intention is that whatever they raise will reflect in some small way the support the author had from people in Ukraine to enable her to tell her story. The author travelled to Ukraine and was made very welcome by many people in the course of her research work.

The Half-life of Snails was published in May by Parthian Books.

Keep up-to-date with Philippa on Twitter @thejackdawspen, and @parthianbooks

For more information, watch/listen:

– the Alternative Stories and Fake Realities podcast

– ‘Going Nuclear’: Philippa Holloway discusses The Half-life of Snails with Holly Porter for Nation.Cymru

– Philippa Holloway in conversation with Zoe Kramer for Wales Arts Review

Read our Get to Know the Author flyer for further information about Philippa Holloway and The Half-life of Snails.

See also our Authors of the Month writing in Welsh.